A student’s potential hinges on their high school grades. Recently, adjustments to DGS’ retake policy have sparked mixed emotions for students and teachers. While many students advocate for the policy, most teachers express concerns, seeing potential drawbacks that could undermine student needs. Ultimately, both students and teachers are striving for a system they believe works best. But, the question remains: why was the policy necessary, and are retakes the solution?

But first–is school meant to foster mastery learning, or is it focused on preparing students for college and the workforce? While these two goals may seem conflicting, a middle ground can be achieved—through retakes. Schools were originally intended to promote mastery learning, enabling students to deeply understand subjects rather than rely on strict memorization. Schools also aim to equip students with lifelong skills essential for their futures. But many factors can decrease a student’s interest in learning.

While there’s substantial evidence explaining why students continue to struggle with grades, the primary focus should be on finding solutions that can temporarily level the playing field for all students while working toward long-term improvements.

Mastery grading has four key steps: determining learning objectives, defining mastery, establishing grading protocols and incorporating flexibility. Students can then achieve a deep understanding of the material–something that can be achieved by retakes in particular as students revisit concepts.

Some teachers argue that colleges rarely allow retakes–but this isn’t entirely accurate. Retake opportunities depend on individual professors, which students can choose based on their needs through tools like RateMyProfessor. Additionally, professors frequently implement flexible grading policies, like allowing students to drop their lowest exam scores or revise assignments for improved grades.

Yet high school students are assigned fixed schedules with little say in their teachers or curriculum, which can exacerbate learning gaps—especially for struggling students who benefit from tailored instruction. Retake policies offer all students the chance to achieve success.

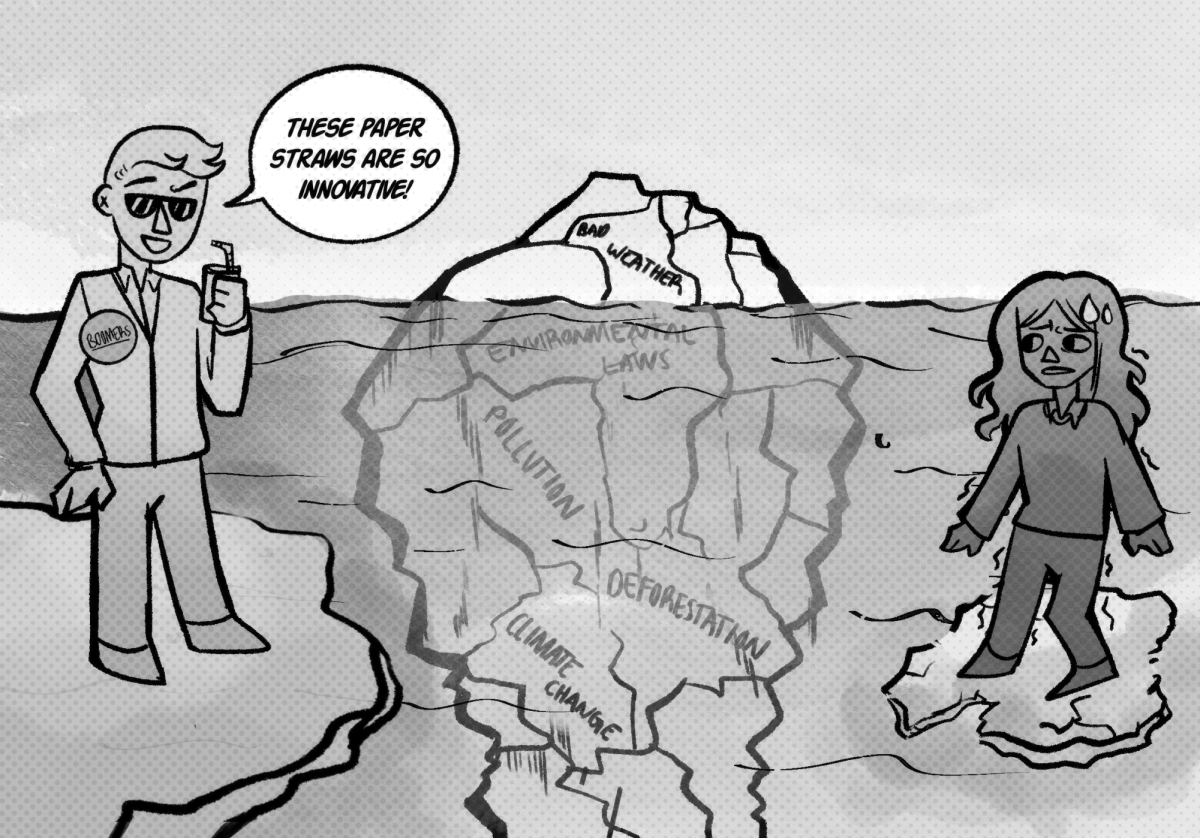

At DGS, retakes have thoughtful restrictions, like requiring all late or missing work to be submitted before a retake is allowed. While some educators find late work frustrating, it’s essential to approach these situations with empathy, recognizing the unseen challenges students may face at home.

DGS also offers fewer honors course options compared to surrounding schools in the area. For example, Hinsdale South High School begins offering weighted World Studies Honors in the social studies department to freshmen and allows students to enroll in

Honors Spanish at Level 2, providing weighted options early in their academic journey (Program of Studies 2025–2026, 2024). In contrast, DGS students must take the unweighted version of Global Connections, and graduation requirements often lack weighted grading opportunities. This disparity places DGS students at a disadvantage when competing for college admissions, as weighted courses boost GPAs and provide students with more opportunities to demonstrate their academic abilities. Retake policies help mitigate this imbalance by allowing students to revisit material and improve their understanding, even if weighted options are unavailable. Through retakes, students can demonstrate mastery of challenging material, which is crucial in leveling the academic playing field.

By focusing on mastery learning, retake policies ensure that all students, regardless of the courses available to them, have a fair chance to succeed. When implemented thoughtfully, retakes equip students with essential academic skills and resilience, preparing them for college and lifelong learning.

In fact, the current restrictive retake policy with its 80% cap hurts the students DGS is attempting to help. Instead of closing the gap between high-achieving and average students, the gap is widened.

High-achieving students inevitably adjust to the higher standards set by this retake policy–whether that means finding a tutor or simplifying studying “harder.” They care too much about the top grades they’re gunning for. Yet this kind of behavior isn’t true for all students, nor should it be expected.

For many students, the current retake policy that was created to help them means nothing–they don’t care enough to retake. These students have already moved on to bigger and better things, causing the gap between students to widen. So, the 80% cap is uselessly arbitrary and contributes little to the academic achievement of the student body, especially towards learning.

As we’ve seen the adjusted retake policy implemented in the first semester, perhaps it’s time to ask whether a student who thinks, “Good enough,” after receiving exactly 80% on a test, is a ready demonstration of a “growth mindset.” Maybe it’s time to consider how teachers who say “grades aren’t everything” to the high-achieving student who wants to retake the test they got an 85% on are actually contributing to the grade fixation that’s so prevalent in our student culture–instead of encouraging learning and a motivation to do better.

We often hear teachers say that retakes only cause more stress and more work. And that’s certainly true to an extent–teachers are obligated to write whole new tests for retakes and spend time grading those retakes. It’s certainly unfair for teachers to allow students to retake every single test, especially if students are already scoring high.

In addition, students have to re-study for the retake–often meeting with their teachers and completing an extra assignment on top of that to be “approved” to retake. We’re not advocating for a free-for-all retake policy, merely one that reframes retakes as having a restricted use, not a restricted percentage. The 80% cap on retakes encourages students to only learn the material to 80%.

The reality is that most high school students don’t have the discipline or the time to challenge themselves past the bare minimum while juggling jobs and extracurricular activities.

Last year, we knew many students who’d thrown themselves fully into the studying process, knowing they had the potential to earn all those points back. Now, all those students have to do is get an 80%. Not a hard ask, especially considering they’re retaking the material.

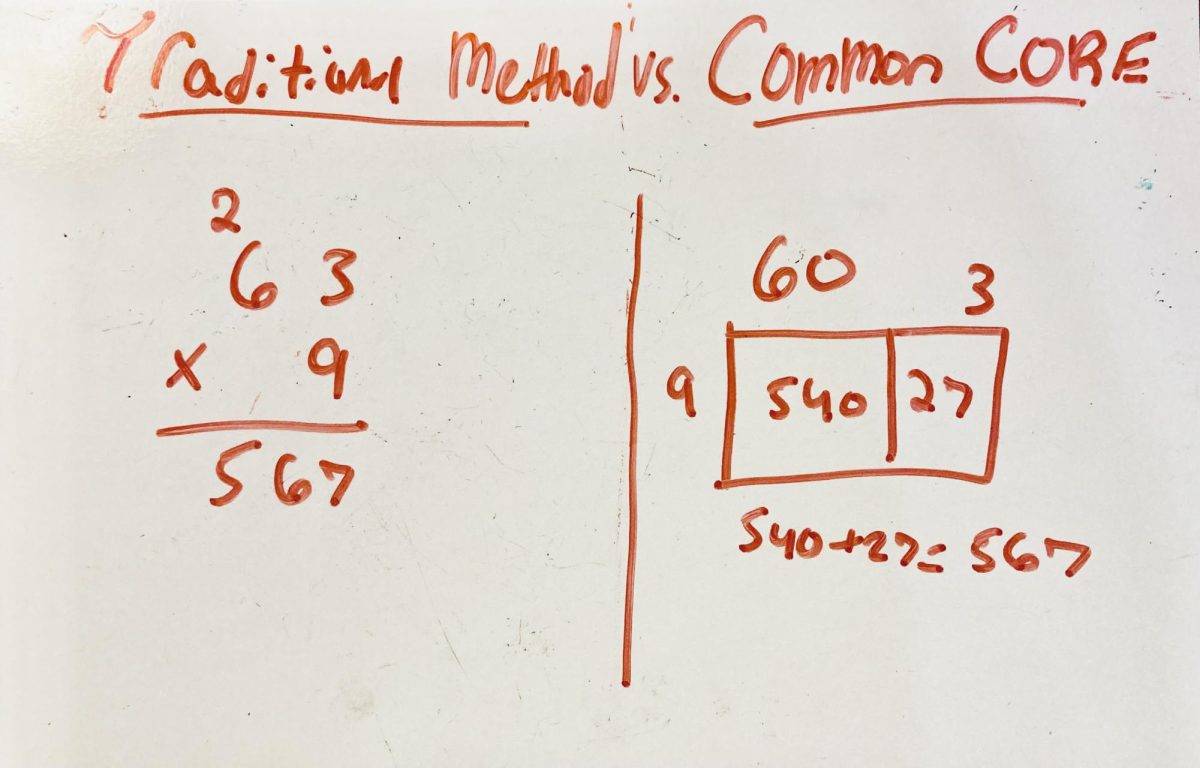

This bare minimum approach again makes students hyperfixate on the percentage, rather than the actual learning at hand. In subjects like math and science, a deep understanding of the material is critical. Yet many students never achieve this kind of understanding, too focused on the letter grade.

At this point, you may be raising points about how retakes result in a lack of discipline, where students who struggle to manage their time can always cash in second chances. That may be true to an extent for STEM subjects (again, why we’re advocating for a limit on the number of retakes, not the percentage), but our current retake policy is even more radical when considering English classes.

In English and humanities classes, revision is a critical part of the writing process. Yet our school has reframed the editing and multiple-draft work that goes into crafting an essay, a poem, or a memoir, into simply “retakes.” How the retake policy is implemented in English classes demonstrates how the 80% cap just doesn’t foster a learning environment.

So yes: there is a time and place for one-time tests. There’s also a time and place for retakes–retakes as a policy that uplifts students’ learning yet supports teachers’ hard work in the classroom. Retakes as a policy that limits the times a student can “take advantage” of the system, yet gives the students full opportunity to demonstrate their learning.

As the administration considers how to move forward with retakes in the future, we hope they’ll keep this in mind–that learning is a series of failures and mistakes, and our school policies should mirror that process.