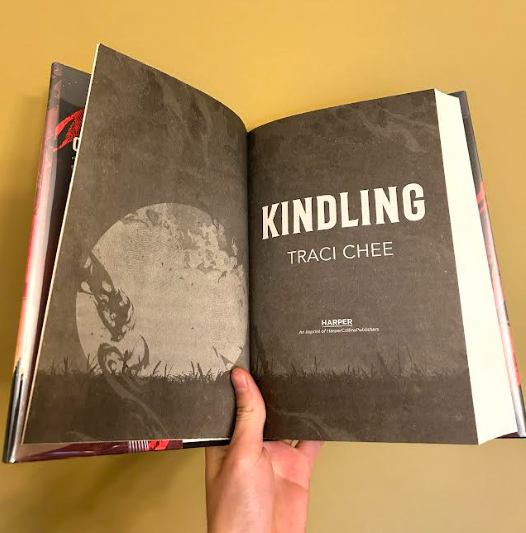

In the modern age, the tragedies of the world are captured for endless re-watches, for countless people to be briefly ensnared by a dramatic headline–or regretfully misinformed through a trite fictionalization. Increasingly, “objective” coverage on violence is sensationalized for optimal audience interest. But “Kindling,” in its interrogation of collective suffering, and later, collective healing, consciously avoids this insensitive handling of difficult events.

Through seven fully realized perspectives and piercing storytelling, author Traci Chee empathetically speaks to the young people of today. “Kindling” is a masterfully rendered novel with minimal flaws.

“Kindling” portrays the story of seven teenage warriors–kindlings, whose power was exploited by their nations for a devastating war. In the aftermath, the kindlings are unmoored, forbidden from using their power and seen as useless by everyone else.

And though the war has ended, skirmishes are frequent in the countryside.

One such skirmish unites two kindlings: Amity, an infamous war hero, and Leum, a gruff but soft-hearted soldier. When they hear raiders’ plans to attack a nearby village, they begin recruiting other kindlings for their cause.

But as all seven kindlings are drawn deeper into the fight, the sacrifices they must make are just as deep–causing them to question their place in a world where their lives only begin and end with their power.

Such fragmentation of identity is revealed in the blunt and clipped prose. Frequently, sentences are cut off with dashes or paragraph breaks. Even more so is Chee’s use of incomplete sentences, grammatically incorrect and jarring in their persistent use.

And even in longer sentences, characters switch abruptly between ideas with their afterthoughts in parentheses. The rare block of text provides relief for the audience, slowing down the narrative with the brief departure from what can almost be called free verse.

Chee’s attention to detail is on full display here: smoother prose is frequent in naïve, innocent Siddie’s perspective, while choppier phrases make up the other kindlings’ perspectives.

However, Chee falters at times; parallels in character development are clear, but at the cost of being on-the-nose. Take Ben, for example, a kindling who desires to be “perfect” throughout most of the novel. Though Chee’s language is intentionally simplistic, in line with the prose throughout the novel, Chee’s usual repetition techniques don’t work well with such word choice.

Although Ben’s character arc has depth, its significance is closely defined by Chee, leaving little to discuss for the audience.

But it is a testament to Chee’s skill how the author voice, narrative voice and character voice are consistently distinct. Chee’s personal style–straightforward, with the occasional use of figurative language–is separate from the reflective, melancholy collective voice of the narrators–the kindlings–which in turn is separate from individual character voices that convey one character’s cynicism and another’s arrogance.

Even the villain gets the spotlight.

It’s the rare occasion that the antagonist’s point of view adds to the emotional and structural complexity of a story, rather than being a one-off monologue plotting against the hero. But in her chapter, Adren, the antagonist, is revealed to be multi-faceted.

Yet the reader’s deeper understanding of her doesn’t shift the focus from the kindlings or the plot. Indeed, Adren’s thoughts during the scene become highly relevant to the themes displayed near the end of the novel.

In allowing space for so many voices, Chee’s story comes alive, rich in context and beautifully told.

Chee’s storytelling also shines in her balance of a well-realized fantasy world with a developed backstory. Although the war has ended for the kindlings, Chee frames their emotional turmoil and the unresolved violence after the war as just as urgent–the reader never feels like “Kindling” would be a more important or “exciting” story if told during the war.

Chee doesn’t fixate on on-page violence for dramatic theme development, instead discussing with integrity the effects of violence on young people.

But perhaps Chee was too focused on the seven kindlings in the end. The fighting scenes at the climax were already powerful because of the physical and mental tolls on the characters, but the minimal emotional interaction with the antagonist failed to carry Adren’s humanity through from her earlier point of view–a choice that would emphasize the complex interactions between those affected by a collective tragedy.

Ultimately, though, Chee’s choice is more realistic: an abrupt but hollow victory, premature deaths and unfinished business.

“Kindling” may not be the hardest read, but it’s a thought-provoking one without a doubt; a four-star novel that could quickly become a favorite.

Chee’s handling of multiple perspectives, a rich magic system and most importantly, sensitive topics, is beyond refreshing. It’s an essential affirmation of young people’s perseverance in the darkest of times.