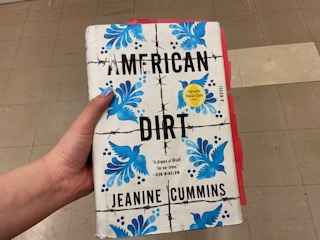

‘American Dirt’ book whitewashes experience of Mexican immigrants

While “American Dirt” is not poorly written, it’s content ultimately lacks depth and therefore I would give it a three out of five stars.

“American Dirt,” written by Jeanine Cummins proves that writing about experiences you can only imagine is never the foundation for good writing. The novel tells the story of Lydia and Luca, the wife and child of a murdered journalist from Mexico, as they attempt to cross the border to the U.S. Described as a poignant, timely novel, it made national headlines for one major reason- Cummins is not a migrant, nor is she Mexican.

In reading the novel, the question for me went far beyond how well written it was, how developed the characters were, how enrapturing the storylines were. As a Mexican-American, the question became–who gets to tell our stories? Can a white woman, with years of research and noble intentions accurately portray the experiences and lives of my people and my culture?

She can’t.

While Cummins is certainly a good writer, the novel lacked honesty and truth for me. In her Author’s Note, Cummins writes that she wanted to tell the stories of the average people who are impacted by the gang violence in Mexico. She wanted to write about the lengths someone, a victim, would go for their family.

That’s certainly noble, but in reading the novel, the story still had undertones of dramatization to it that made it hard to differentiate from a show like “Narcos” or “La Reina del Sur.” Yes, Lydia is running from the cartel that murdered her husband instead of running that cartel, but the novel still felt like I was reading the script for an action movie.

If Cummins wanted to portray how the average Mexican is impacted by the cartel, then mistake number one was making Lydia have a close friendship with “La Lechuza” (The Owl) who is the leader of the gang that is terrorizing her hometown of Acapulco. The average person does not mistake the leader of a major cartel for some regular dude in her bookshop, consequently have a meet-cute with him, and then form a friendship over their love of books.

For me, Lydia, the essence of her character, the way she carried herself and the things she did- owning a bookstore, joking about needing coffee to survive- were all things I would have expected from an American character. No, Cummins did not have to create characters that were familiar to me in particular, but these characters who were supposed to be Mexican felt nothing like any Mexican person I’ve ever met.

My great-grandmother had 16 children. She had 44 grandchildren. I know a lot of Mexican women, and the main character of this novel was nothing like any of them.

Ni un poco. Not even a little.

It gave the impression that had Lydia been authentically Mexican, her story would not have been easy to digest or important enough to tell. A common theme when it comes to the stories of Mexicans- if they are not similar enough to an American, then the story becomes foreign difficult to read and therefore empathize with. The stories of others should not have to be familiar for them to be important, nor should they be comfortable in order to solicit empathy from those reading it.

The other major issue that I had with the novel was Cummins’ inability to effectively use the Spanish language. Her usage of it within the novel felt forced, a failed attempt to create an image of Mexico and its people. As a Spanish-speaker, I know that the words mean different things when I switch between languages.

Using a direct translation, or calling sandwiches “tortas” instead of just saying it in English, cannot truly convey what those words mean to those of us who use them. There’s a potency to words in Spanish, a well of reserved power in using them correctly, that could have elevated this story. It could have given it honesty, relatability and authenticity.

A non-native Spanish speaker can’t do that.

There were only two things that I appreciated within the pages of “American Dirt”- Cummins’ portrayal of Mexican journalism and the complexities of the cartel. Lydia’s husband is murdered for his ruthless and truthful investigations into the cartel. His job is described as difficult, dangerous, righteous.

To be a journalist in Mexico, you either have to lie, or live with a target on your back. It is one of the most deadly jobs in the country. Cummins brief acknowledgement of this was refreshing to see.

For a fleeting moment, when Cummins first introduces “La Lechuza,” there is a brief description of how he is intelligent, driven, ambitious, eager to bring tourism and life back to Acapulco. He is not simply a murderous, power-hungry, cold-blooded killer who terrorizes the citizens of Acapulco. He lowers the amount of violence, invests money into schools and hospitals, aims to get the city back on its feet.

Therein lies the complexities of the cartel. Any Mexican can tell you that the cartel is deadly, but it is organized, and sometimes, it gives back to the communities it overtakes. There are cartel leaders who have flashes of empathy, who give back more aid to their villages than the government does.

Just ask anyone who lives in La Tuna, Mexico how they feel about Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman. Yes, he’s the most powerful drug trafficker in the world, but he’s also provided food, shelter and basic resources to impoverished peoples who’ve received nothing from the government. To some, he is as much a hero as he is a murderer to others.

An expansion of either of these ideas would have given the book the depth it attempted to have, but because they were fleeting, the book seriously lacked meaningfulness for me.

Anyone can tell you that a white woman probably doesn’t have the agency to write the story of a Mexican migrant. My disappointment over this novel however, isn’t aimed mainly at Cummings for wanting to write the stories of migrants and their suffering. In fact, I appreciate her interest and willingness to try and tell those stories.

My disappointment instead lies in the fact that we ourselves have not demanded the spaces to tell our own stories. As Mexicans, we cannot wait for a white woman to tell our stories. We must stand at the doormat of this country and demand to not only be let in, but demand the opportunity to share our perspectives, our trials and tribulations.

I understand that asking any migrant to tell their story is asking no simple thing. Many still live in fear, afraid of being discovered and sent back home, destined to make the treacherous journey all over again. Most are at the bottom of the social ladder, lost in a foreign land, unable to speak the foreign language that could make their story heard.

Pero si queremos que nuestras historias sean honestas y auténticas, tienen que venir de nosotros. Tienen que venir de los labios que han sentido el frío del desierto de noche, de los ojos que han visto las pistolas de la migra, de las manos que han agarrado La Bestia, de los pies que han cruzado la Frontera. Tienen que venir de las voces que han cantado el himno nacional, de las bocas que han formado la palabra esperanza, de los corazones que entienden lo que es amar el país de cual vienes al mismo tiempo que lo estas dejando por otro.

(But if we want our stories to be honest and authentic, they have to come from us. They have to come from the lips that have felt the cold of the desert at night, from the eyes that have seen Immigration’s guns, from the hands that have held “La Bestia”, from the feet that have crossed the border. They must come from the voices that have sang the national anthem, from the mouths that have formed the word hope, from the hearts that understand what it is like to love the country you come from while at the same time leaving it for another.)

I respect the attempt that Cummins made in writing “American Dirt,” but overall the book could never truly achieve its goal of accurately portraying the suffering and hardships that a migrant goes through when crossing the border. No matter how much research, no matter how many visits to Mexico a writer takes, the story will always lack so long as she is not part of the fabric of what she is writing about.

Taila Lee • Mar 24, 2020 at 11:26 pm

Hi there! I’m a student journalist from Woodside, California, and I came across this review on Best of SNO. It moved me so much that I wanted to comment on the review on the original website 🙂 I can tell you put a lot of work into this review, and the line “Tienen que venir de las voces que han cantado el himno nacional, de las bocas que han formado la palabra esperanza, de los corazones que entienden lo que es amar el país de cual vienes al mismo tiempo que lo estas dejando por otro” is very empowering. Thank you for writing this.