Parents v.s. teens: Children’s critiques of their caregivers

Between privacy, trust and support, teenagers and their parents may never see eye-to-eye but they still share a bond of care.

December 6, 2021

Gen Z’s roadblock to receiving emotional support: Parents’ aversion to therapy

As of 2021, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, over 4.4 million Gen Z students in the United States have been diagnosed with anxiety. Gen Z’s access to therapy has increased over the years, but some parents are resistant to the cause.

DGS Licensed Clinical Social Worker Tracey Salvatore is one of the many professionals hired to aid students. She speaks on how DGS provides help to students who might feel as though they can’t access aid due to a family with an aversion to therapy.

“I mean fear comes from what we don’t know, and worried thoughts can be really damaging. Just come talk to somebody or talk to a friend that talks to somebody so that they can help encourage you,” Salvatore said.

Salvatore builds on the ways students could get help by mentioning the Counseling and Support Services at DGS, which is a department found in the school or through the DGS website.

“We work here for a reason. We work here because the district understands that you are whole people and you’re not just about a report card, you’re not just about academics and so we truly do want to support the social and emotional needs of each student,” Salvatore said.

To help students who can’t access the DGS Counseling and Support Services during the school day, Salvatore mentions the programs and services outside of school that therapy agencies offer.

“Students can access mental health support from agencies, like get therapy without parental consent for up to five to seven sessions. Most often students do access therapy in the community with parental involvement, but there are occasions where parents will not consent, for a variety of reasons. That young person can access at least limited services on their own too,” Salvatore said.

As a senior at DGS, Catherine Gadomski is an open advocate for students receiving therapy. She explains why she believes that every student that wants to go to therapy should have the option to do so.

“I think the benefits are helping find yourself because sometimes you can’t do it on your own and sometimes you need the help like putting the puzzle together,” said Gadomski.

Despite some families’ distaste for Gen Z’s want to get therapy, the benefits as told by students and professionals outway the criticisms.

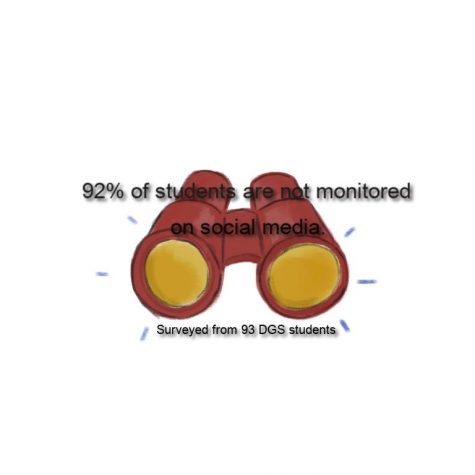

Privacy: The push and pull between rights and privilege

According to ABC News, the average teenager spends more than seven hours on their phone every day. These devices often hold a great deal of personal information for their user. This detail, however, does not stop 60% of parents from monitoring their children’s phones (PEW

Research Center).

Methods of auditing cell phones have become as varied and advanced as the handhelds themselves. Parents have an array of options, such as the popular location-tracking app Life 360. Or, if they have an Apple device, parents can go right into Settings to utilize Screen Time, a program that allows for the device user—or user’s parent—to track and limit the time spent on certain apps.

Many parents choose more than one monitoring tool when managing their kids’ phone usage. Sophomore Nathan Kulovany discusses the ways in which his phone is supervised.

“When I get in trouble, [my dad] will go through all my text messages, my camera roll, my Snapchat…I think it becomes inappropriate when he starts going through my messages [with friends]; I think that’s not fair to me or the person who’s texting me,” Kulovany said.

Kulovany’s father, Michael Kulovany, comments on the reasons behind why he monitors his childrens’ phones.

“I think that parents do have a right to infringe [on that privacy] if they feel that their kids may be doing something that could harm them,” Kulovany said.

It is widely agreed that privacy is crucial to a child’s development. It allows them a first taste of independence and room to explore their identity. Monitoring a teen’s phone habits can cause tension between child and parent if the child feels their privacy is being compromised (Psychology Today).

There is, however, a middle ground to be reached when monitoring phone usage. Kulovany notes that Screen Time, a relatively non-invasive program, has been beneficial for him at times.

“I don’t see a problem with setting a ‘bedtime’ for your kids…I also think it’s pretty effective, like when I get grounded my dad blocks everything and it motivates me to do better because I literally can’t do anything when my apps are all off,” Kulovany said.

Privacy is a delicate line to toe, as parents and teens have found. It seems that a child’s cellular privacy is dependent on whether or not their parent trusts them not to abuse it. But, that conclusion in itself begs the question: Is privacy a right or a privilege?

The family battle over trust in teens

The battle of trust between parents and teenagers is a tale as old as time: “Where are you?” “What are you doing on your phone?” “Who are you talking to?”

The lack of trust on either side of a parent-child relationship can be a result of various behaviors, such as lying, not keeping promises or behavioral actions. These implications, however, can be built back up, through the challenge of gaining trust.

Senior Gabriela Rodriguez believes that trust is important in the development and maintenance of a parent-child bond.

“I think it’s all about how the relationship between the kid and the parent is. If the relationship is strained, then, of course, there’s going to be that lowered level of trust, that could be lack of communication,” Rodriguez said.

Communication is significant in forming trust between parents and teens, but it requires cooperation from both sides. Senior Kelsey Casella shares how she began talking and being more honest with her own parents and has seen positive results.

“My parents put a lot of trust in me because I basically tell them everything. They would rather me be honest with them and know what I’m doing or where I am, than me having to lie to them,” Casella says.

On the other side of the fight, DGS parent Nancy Bifulco believes that the idea of trust between a parent and child should come from both sides.

“It’s not just important for parents to trust their children, but for the child to trust the parent. They need to be comfortable with going to them and talking to them about anything. That little change in a relationship can make a huge difference,” Bifulco said.

Trust is a difficult thing to form in a relationship, with many trials and tribulations; however, when a parent and their child actually take time to sit down and communicate all the unsaid words, a relationship can grow even stronger.

Parenting through the generations: How a parent’s upbringing affects how they raise their own children

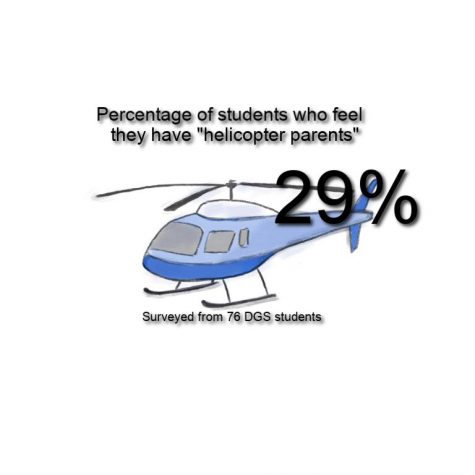

The children of Generation Z have been the subjects of a dramatic shift in parenting style within the past 20 years; when juxtaposed with how their parents grew up, the way Gen Z has been raised is almost completely unrecognizable to that of previous generations. Many experts today attribute the shift in parenting style to technology and increased access to information. While this may be true, many teenagers feel that their parents are overstepping boundaries and invading their privacy.

DGS parent George Tomecki recounts his experience as a child raised by two immigrants during the eighties and nineties.

“My parents came here from Poland with not a dollar in their pocket or knowing a word of English. They worked, put food on the table, and provided for the day to day necessities but there was no talking about emotions and they never took what we thought or wanted into consideration. They were more dictator with corporal punishment,” Tomecki said.

When comparing his childhood to how he parents his own children, Tomecki believes that his parenting style is the opposite of his parents. He also detailed how he has utilized technology within his parenting.

“I would describe my style as authoritative parenting which is the idea that it is better to allow children to struggle through and make mistakes. I have tried to utilize technology as a tool to help our lives,” Tomecki said.

Junior Skyler Tomecki shared her thoughts on her parents’ use of technology when parenting.

“My parents are a family that uses Life 360 and they definitely rely on technology to communicate and track where I’m going. It’s not necessarily due to a lack of trust; I think they are just very nervous and want to make sure I’m okay. I think sometimes it can be an invasion of privacy but I know it’s just because they want me to be safe,” Tomecki said.

DGS social studies teacher Tracy Culcasi vocalizes if she believes parents are effectively setting their children up for success based on her observations over the course of her teaching career.

“I think parents today are trying to prepare their children as best they can for success in the future, but the world is rapidly changing and the skills that students need to be successful are changing too. I think that parents today are much more hands-on than they were in previous generations,” Culcasi said.

As the modern parent continues to be more hands-on, it seems there is a delicate balance between parents’ involvement in their child’s lives and invasion of privacy at the expense of their children.