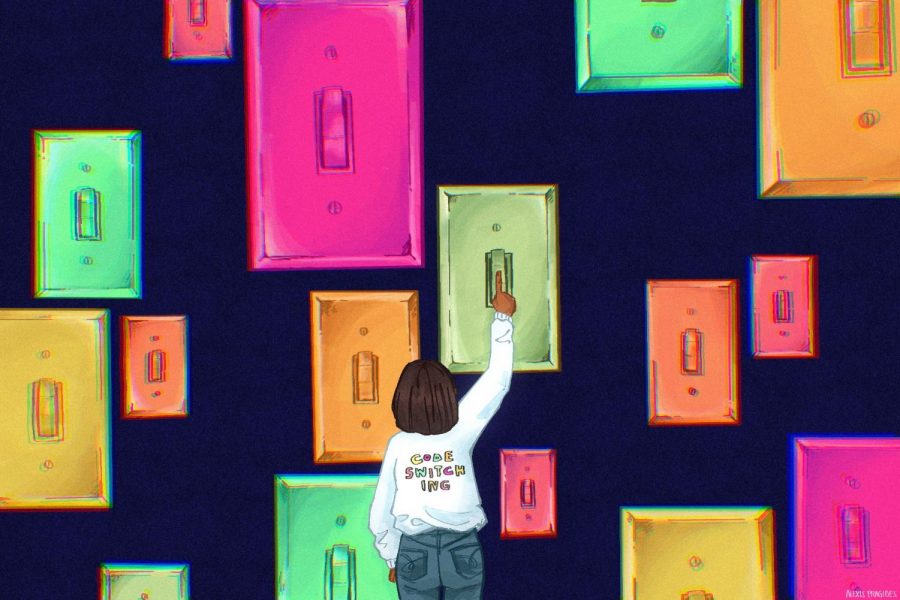

Acceptance over authenticity: Students and staff of color share their experiences with code-switching

January 22, 2021

As people of color navigate through different spaces, many say they feel the need to switch between different ways of talking in order to be perceived in a positive light.

Merriam-Webster defines code-switching as “the switching from the linguistic system of one language or dialect to that of another.” For those from minority communities, this may come in the form of switching from African-American Vernacular English or a native language to standard American English in order to more easily assimilate.

Some say that the danger in code-switching lies in the fact that it forces an unfair choice for people of color; either they change their way of speaking to appease those around them or talk naturally and risk being seen as unprofessional.

Everyone’s experience with code-switching is different, usually arising from everyone’s equally unique personal identity. An example of this can be seen in senior Aamari Taylor, who identifies as Black, feeling that her race has played a key role in shaping her identity.

“Being black definitely impacts my identity — well, being black in America I should say… I’m my own individual and to know that in some cases I won’t be treated that way because of my skin is frightening. At the same time, all this makes me proud to identify as Black because we were held back for so long and still continuously moving towards equality,” Taylor said.

At times, negative stereotypes have caused people of color to not proudly claim their identity. Associate Principal Omar Davis, who identifies as Black, spoke on how he did this growing up.

“When I was younger, I was less concerned with my Black male identity; it was something that you didn’t want to call attention to, you didn’t want it to go before you in a room because of some of the negative connotation that comes with it,” Davis said.

For Taylor, although she remains proud of her racial background, she acknowledges the stereotypes that come with being Black in America, something that she keeps in mind when she’s at school.

“I feel like I have to code-switch at school. It became natural for me to switch up the way I talk and act when I’m around certain people… I think I do this because I don’t want to be treated differently because of the way I naturally talk or carry myself, so when I first meet people I present myself based on the environment, not what’s expected of me due to stereotypes,” Taylor said.

Senior Winniegold Gyimah-Boakye, who identifies as a Black African, describes how when she moved from her home country of Ghana to England, the way she talked with her English classmates left her alienated. In her case, her natural accent made it impossible for her to code-switch, creating situations where she couldn’t communicate with her classmates.

“I’ve had situations where I felt no one understood me — quite literally. I ended up wondering what was wrong with me or that I needed to change, especially around the time I left my home country to a summer school in Leicester, England,” Gyimah-Boakye said.

These experiences in not being understood by her peers as a result of her accent are something common among minorities speaking to those from other communities. This is something that has shaped how she uses language, as over time she has naturally found herself code-switching in unfamiliar situations.

“It has become more of a subconscious thing. I am bilingual so when I am around my friends who know me well enough, they do not mind the casual word slip-up in my language or Ghanaian mannerisms. However, when I take my surroundings into consideration and I feel as though I am the only ‘different’ one there, my mind works on its own and produces different tones and pronunciations. I can’t help it; it has become ingrained in who I am,” Gyimah-Boakye said.

For many people of color, code-switching that has become ingrained into their daily conversations is born out of necessity as they worry about how their words will be perceived. Taylor spoke on how the Black community specifically is perceived when they don’t code-switch.

“A lot of times if black people don’t code-switch the credibility in our words can be negatively affected. When you already have to walk around with the stereotype on your forehead that you are not as intelligent as other people it feels necessary to change how you act and talk around people,” Taylor said.

English teacher Nathaniel Haywood, who identifies as Black, shares in Taylor’s sentiment that Black people’s words and accomplishments are viewed differently because of their race.

“[My race] is at least partially responsible for my work ethic and perfectionism since I grew up always being told that as a black person I would have to work twice as hard to get the same thing as everyone else,” Haywood said.

A Harvard Business Review experiment affirms the assertion that Black people who don’t code-switch are perceived differently than they would otherwise. In the experiment, Black participants who code-switched were viewed as more professional by their White peers while Black members of the experiment viewed them as being inauthentic and unprofessional.

Taylor disagrees with this assessment that code-switching is inauthentic, instead arguing that code-switching has utility in her life, allowing her to control how others perceive her.

“With me it seems like a life skill so I don’t think it’s a problem because it comes naturally. I just adapt to the environment that I am in. I like being in control of how people see me,” Taylor said.

Gyimah-Boakye agrees with Taylor, viewing it as something she’s developed over time rather than something that’s been forced upon her.

“I personally don’t believe code-switching is being deceptive or masking who I am; in fact due to my experiences and development as well as the different accents I grew up with, it is a part of me. It’s a subconscious habit,” Gyimah-Boakye said.

Still though, as the situations of when to code-switch or not blur, some students report facing repercussions for talking as they naturally would. Senior Jimena Gomez, who describes her ethnicity as Mexican-American, recounted a time that stood out to her because she didn’t code-switch.

“A memory I vividly remember was in the 3rd grade when a teacher got me in trouble for speaking Spanish in the classroom,” Gomez said.

Even during times when she didn’t face direct punishment, Gomez says there have been times where not code-switching has brought about uncomfortable situations.

“I sometimes surprise classmates when I [speak Spanish] as they seem to always tell me I don’t look like I’d speak Spanish. Every time I get this comment it always makes me feel out of place,” Gomez said.

Gomez continued, stating, “I remember my sophomore year in my PE Leading Training class a challenge Mr. Terry set up for me was dealing with a student who only spoke Spanish. The student was a friend of mine so we both knew our speaking abilities but another classmate came up to us and told us how they didn’t know we spoke Spanish because we didn’t look the part.”

With all of these situations in mind, Haywood agreed that there is room for improvement in the walls of DGS, emphasizing that acceptance of who students are is key. Haywood describes what he recommends teachers do to create a more inclusive classroom.

“Teachers should look to understand what their students are expressing, as opposed to forcing students to express their thoughts the way with which the teacher is most comfortable. At the same time, there is danger in assuming that someone code switches just because they are a minority because that also reinforces stereotypes. Accepting students as they are and reinforcing their value is critical,” Haywood said.

Gyimah-Boakye pointed to potential ways teachers can establish welcoming environments so students didn’t feel the urge to code-switch.

“They could be inclusive of other cultures: rephrase questions so they can be answered by

anyone regardless of background or identity. They could be respectful of other cultures and ask for pronunciations of certain cultural words when necessary. If a student’s name is foreign, they should at least attempt to learn the correct pronunciation; ask before giving a ‘foreign’ name a nickname,” Gyimah-Boakye said.

Haywood feels another solution is ensuring that students have the ability to feel comfortable using their own voices and bringing their diversity to the classroom. By creating spaces where students of color don’t feel the need to code-switch, Haywood hopes that students are able to express their authentic selves.

“The expectation just needs to be set that it’s about what you’re saying, not how you’re saying it. At the same time, emphasizing a writer and speaker’s authentic voice is important. Students should not be carbon-copy, cardboard cutout automatons, they should be their own unique selves,” Haywood said.