Student diversity is shown through the different languages at DGS

January 28, 2020

DGS is rich in culture and diversity. The student population in 2019/2020 consists of 57.1% white students, 20.5% Hispanic students, 11.7% black students, 7.4% Asian students and .01% Pacific Islander and American Indian students. Not many people think about how many different languages are spoken by the students and staff here. Speaking more than one language can bring hardships, but it can also expand one’s friendships, knowledge and visions of the world. This was expressed by many of the multilingual students seeking to bring more cultural awareness to DGS.

Multilingual and multitalented: Benefits of speaking more than one language

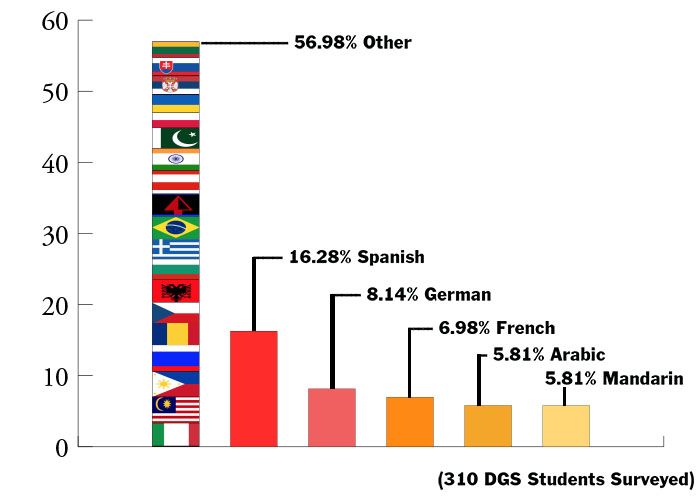

A Blueprint poll found thatover 30 different languages are spoken among DGS students.

According to a US Census survey from 2011, 60.6 million, or 21%, of Americans speak a language other than English in their homes, a statement which is true for many DGS students. However, despite the growing prevalence of bilingualism and multilingualism in America, the benefits can often be overlooked.

Senior Frosina Kostadinova’s roots lie in North Macedonia, but her language abilities extend far beyond one non-English tongue. Kostadinova speaks six languages: English, Macedonian, Serbian, Bulgarian, German and Korean. She explained that one of the biggest benefits to knowing so many languages is the amount of diverse friendships she has.

“I’ve made a lot of friends in other countries, and I think it’s really interesting to learn about more cultures,” Kostadinova said.

Senior Hewane Melkie speaks the Ethiopian language of Amharic in addition to English and believes that the benefits of being multilingual are quite profound.

“[Being bilingual] has given me more of a grasp on multiple perspectives. American ideology, for the most part, is very ‘freedom,’ and for the most part liberal. We believe in independence, but Ethiopian culture is very traditional and [grounded in] what’s ‘right.’ There’s no such thing as a right or wrong version: there’s just an expected way,” Melkie said.

Social studies teacher Elaine Marinakos is the daughter of two Greek immigrants and is fluent in both Greek and English. She expressed that, despite her first exposure to language being Greek, she had little difficulties when learning English.

“I went into kindergarten as an ESL student. Greek was the primary language spoken in our home, and we had just spent the entire summer in Greece prior to my starting school, so my exposure to English was limited. I was a fast learner and was back in the regular classroom within a month,” Marinakos said.

Despite her attempts to instill the value of their language and culture in her children, Marinakos’s three children do not possess the same skills with the language as she did when she was their age.

“With my eldest son, we were very good at speaking to him only in Greek as a baby, but eventually he went to school and English became his primary language and the language he chose to use with his siblings. All three kids went to Greek school for a few years, and they have a basic understanding of Greek, but speaking is a bit more challenging for the two younger ones,” Marinakos said.

In addition to students’ fascination with her speaking Amharic, Melkie noted that her culture is also often fantasized, rather than understood, which does have an impact on her life.

She shared the importance of monolingual English-speakers being tolerant and not glorifying other cultures, and noted that such glorification often has harmful effects on those whose culture is being idolized.

“For students just be mindful of how you react to things, and be mindful of where your surprise is coming from [when learning about other cultures]. Be mindful of how that surprise comes out and how it is perceived,” Melkie said.

Struggles of being multilingual

“I think that speaking another language is important because it allows you to connect with more people around the world,” Karanakove said.

At DGS many students come from different cultural backgrounds and have to adapt to expectations while conforming to an American society. Part of adapting includes learning English. Learning a second language is challenging for individuals because they experience two different cultures at once.

Sophomore Yamil Ortiz moved from Puerto Rico to the United States in his freshman year. He grew up speaking Spanish and arrived at DGS unable to speak a lick of English. Ortiz explained how his personality was negatively affected upon arrival at an American school.

“Freshman year, I felt attacked because I received disrespect from peers since I did not know how to explain myself and speak with them. In Puerto Rico I was very social, but when I came here, I closed myself off so that I wouldn’t make mistakes and have people laugh at me,” Ortiz said.

Senior Andre Beikircher learned Czech as his first language along with German. He notices the cultural differences between his home and school life in comparison to those peers. Beikircher noted the contrast between how he was raised versus his American peers.

“When I was growing up, I didn’t feel I could relate to most people at my school, which made me feel different. I think other kids around me didn’t understand our cultural differences. I noticed the contrast between peers who lived in identical suburban houses and how they spoke only English at home,” Beikircher said.

Students who speak a different language at home often have to switch languages when at school. This is difficult due to the constant change in communication that many American students do not have to experience. Beikircher disclosed his perspective on how he communicates at school versus at home.

“In my house we speak more Czech than English. When I get to school, I switch to speaking English, which is a major contrast. It can be challenging because it is a back and forth switch between languages,” Beikircher said.

Ortiz revealed the common stereotype he faces coming from his Puerto Rican background: he explained people often assume his ethnicity because he speaks Spanish. Ortiz noted it is important that people avoid forming assumptions before they know the facts.

“I think this is not only my problem, but other Puerto Ricans have this problem. I think Americans think I am Mexican just because I speak Spanish, but that is not true. It is mean when you assume someone’s ethnicity without getting to know them,” Ortiz said.

Students coming from a different culture are pressured to fit in with their peers around them and quickly adapt to a different lifestyle. However, Sejko noted that students should not have to change themselves to conform to the stereotypical vision of the ideal American.